This article is part of INTERLINKED, a series where we speak with industry experts who influence the making of games like our sci-fi RTS CHAOTIC ERA.

Sign up for our newsletter here or follow us on Twitter to dive deeper into the worlds of artists, game developers, and more.

Alex Connolly is the kind of artist whose work makes you nostalgic for memories that may have never existed.

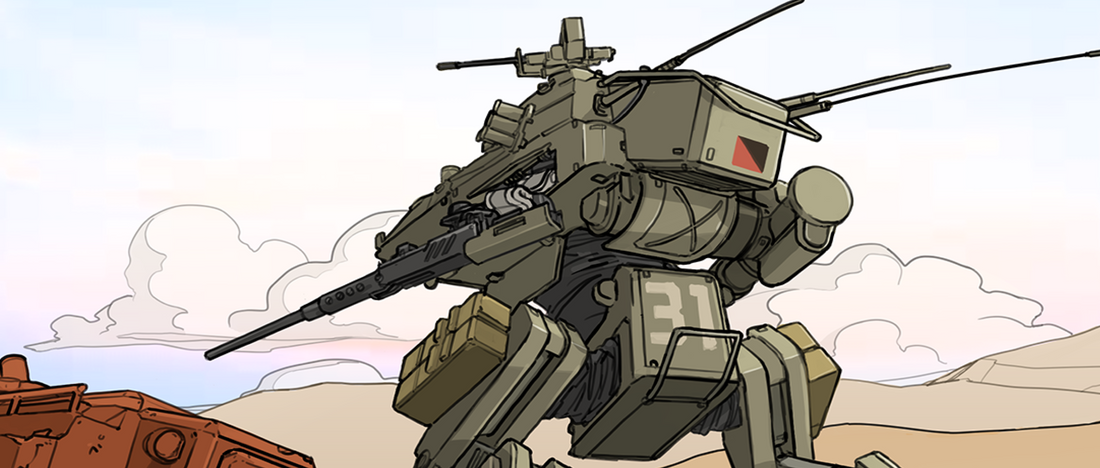

Effortlessly blending the crunchy and chunky mechanical wonders of old school, hand-drawn anime with the bright and inky comic work of artists like Moebius, a Connolly piece immediately strikes you with a sense of familiarity; like looking at a screenshot from a mecha VHS tape that you thought may have been a dream.

That's how Alex first came onto our radar: With some of his brilliant mech concept work gracing our Twitter feed as an early follower of CHAOTIC ERA.

Today, we're delighted to be able to chat with him about the influences behind his work. And to dig into the reasons why humans can't stop daydreaming about mechs.

Today, we're delighted to be able to chat with him about the influences behind his work. And to dig into the reasons why humans can't stop daydreaming about mechs.

Alex, your style has always reminded me of that golden age of late 80s to mid 90s mecha anime; I'm curious what you would say your primary influences are?

That era of Japanese animation is a colossal inspiration, with names like Shōji Kawamori (Macross, Patlabor) and Kunio Okawara (Armored Trooper VOTOMS) being hugely influential. There's just something about the way those guys cooked up fantastic designs with a plausible tilt. The idea of elaborate machinery being fallible and having shortcomings makes for compelling storytelling - be it the inherent dangers of piloting a Gundog or the financial bureaucracy of maintaining an AV-98 Ingram.

That era of Japanese animation is a colossal inspiration, with names like Shōji Kawamori (Macross, Patlabor) and Kunio Okawara (Armored Trooper VOTOMS) being hugely influential. There's just something about the way those guys cooked up fantastic designs with a plausible tilt. The idea of elaborate machinery being fallible and having shortcomings makes for compelling storytelling - be it the inherent dangers of piloting a Gundog or the financial bureaucracy of maintaining an AV-98 Ingram.

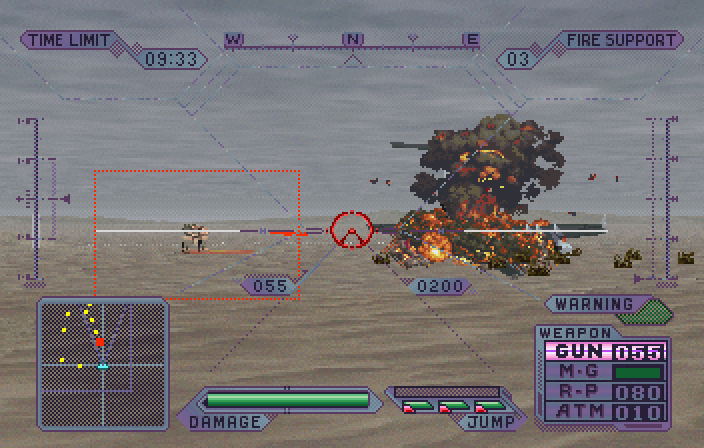

Armored Trooper VOTOMS

Scions of the Japanese 'Real Robot' design school like Junji Okubo (Steel Battalion, Industrial Divinities) and Tahahiro Kawano (Lost Planet series) are big touchstones. Okubo especially strikes such a great balance between flair and functionality; equally proficient in crafting fresh war machines as he is in designs that wouldn't look out of place alongside pushback tugs.

Art by Alex Connolly

It's also very hard to mention Japanese mecha doyans without noting the trusty, rusty and busted scratchbuilt power of Kow Yokoyama and the Maschinen Krieger milieau. A timeless aesthetic of exposed engines, hydraulics and cramped, fire-prone cabs.

Outside of Japan, there's a lot of inspiration from heavy equipment development over the 20th century. It's a treasure trove. If there are a couple of books you must have on your shelf for mechanical design inspiration, it's Eric C. Orlemann's two-part photo history on the machines of R.G. LeTourneau. Sixty years of incredible technological experimentation made real, from Great Depression era graders and scrapers to gigantic land trains tasked with installing radar stations in the Arctic circle.

The design through-line here is a preference for the ungainly, the awkward and no magic mechanical bullets.

What do you think it is about mechs that makes them so fascinating?

I suppose it all stems from power fantasies, which is both a good and bad thing.

The semiotic associations of human physiology and ancient or medieval armours, incomprehensible strength and immense capacity for violence loom large, going hand in hand with stories of conquest and subjugation. While there might be arguments made for regional differences -- Eastern preference for lithe anthropomorphism (Gundam, Neon Genesis Evangelion), Western depictions akin to walking tanks (Battletech) -- it's still two sides of the same fantasy coin.

Art by Alex Connolly

However, they're still able to retain an element of humanity, because their 'heart' as it were remains their operator or crews. And while the rule of cool is always present, I think the most successful mecha properties shine when they treat these ornate constructs as just another tool. In the same way a lorry or a delivery van is seen as background noise in an urban environment, the diffusion of prestige when it comes to mecha is why I've a lot of time for the likes of Patlabor, or where Front Mission treats its coterie of Wanzers as just another part of statecraft.

Art by Alex Connolly

Arguably, a larger percentage of Evangelion fans are there for the teen drama!

But for most people, it's a fascination that undoubtedly stems from the same part of the brain as train or aircraft enthusiasm. Big, complex creations that maximise our capabilities and go really, really fast!

You've had the opportunity to work on a number of different types of projects over your career: Is there any concept work you would want the chance to do professionally, but haven't yet?

I'd love to work on some mech-themed video game, or any sort of game that features chewy mechanical design.

One more mech question: What would you say are the greatest mech games of all time?

Wow, that's a tough one. It's a real smorgasbord. For the sake of interest, I'll skirt the obvious touchstones like MechWarrior 2 and the Front Mission series and list three genre favourites.

Terra Nova: Strike Force Centauri (LookingGlass Technologies 1996)

Some might argue it's not a true mech game per se, but as a hardsuit squad game, featuring all the crunchy interface kit a Heinlein or Haldemann fan could want, Terra Nova is hard to beat. Where other titles' technology is often superfluous window dressing, this was a tactile future soldier experience. Sensors, drones, deployables, squad delegation; it really did feel like you were encased within a million dollar armoured suit of military-grade electronics. In a genre where many outings don't do much with the systems being 'has big gun, shoot big bullets', Terra Nova rides that delicate line where fun meets manageable complexity.

BRAHMA Force: The Assault on Beltlogger 9 (Genki, 1996-98)

BRAHMA Force caps off Genki's trilogy of mechanised dungeon runners (quadrilogy if you count the Sega Saturn's Robotica) on the Playstation, and is arguable the recipe perfected. It's a heavy, inertial, first-person mecha driver, constrained to the corridors and antechambers of the derelict space station players are tasked to explore. What makes this one special is a sense of weight and an overenthusiastic HUD, brimming with targeting reticules, ammunition counters, elevation rules, maps, additional unit icons; a frisson of techno goodness that condenses all the things you like about Terminator Vision, or when RoboCop scans a roomful of criminals. Paired with the crunchy fidelity afforded by the PlayStation's hardware, BRAHMA Force is a beautiful forward-looking time capsule. Oh, and the starring mech was designed by none other than Makoto Kobayashi.

GunGriffon II (Game Arts 1998)

When I'm playing GunGriffon, I'm 'driving' GunGriffon. Few can claim to hit that sweet spot of weight and speed like Game Arts' military mecha outings. It gets the scale just right, features the busy HUD we love, but when you're moving around on the battlefield, you feel equal parts gunship and battlesuit. Perhaps a product of its semi-arcade mission design, but everything is fluid without being weightless, and heavy without being lethargic. These concepts are nebulous, but if you know, you know. And Game Arts knows.

I could go on and on with a ballooning list of honorary mentions, but those three titles highlight what I feel is important in mech game design; nods to systems complexity, interface, and inertia.

------

Before you go:

- Share this post or leave a comment.

- Wishlist Chaotic Era on Steam.

- Follow us on Twitter.

1 comment

EHZ JDYIJEM pjdIdJ wcZzGJ